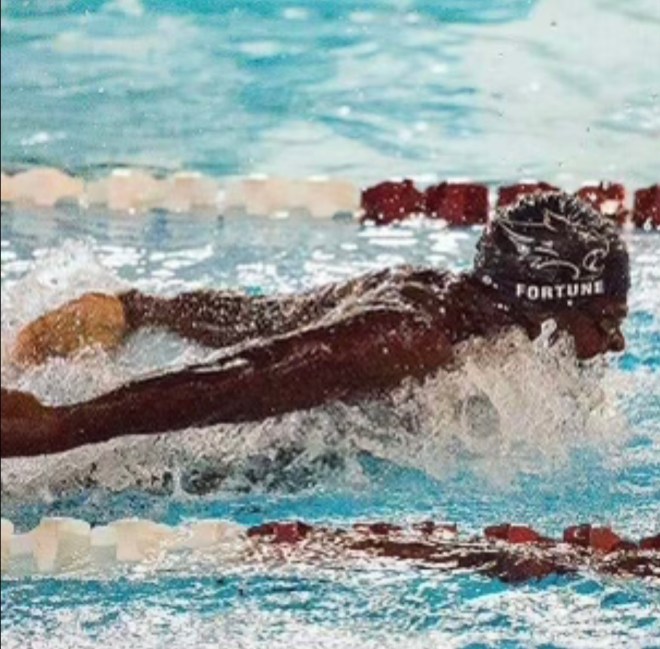

C.J. Fortune couldn’t hide under a uniform when he stepped on the deck before a race. Among a sea of swimmers who didn’t look like him, his bare, dark arms and legs screamed other.

His mother, Nina Fortune, said it was sometimes hard for her son to be one of the only Black people on the FLEET Swimming team in Cypress, Texas. On some occasions, she said, his peers confused him for one of their other Black teammates and called him the wrong name.

“People didn’t see his face, they just only saw the color of his skin,” his mother said.

Now a University of Texas junior, Fortune loved the water so much he spent 13 years with FLEET and served as the captain of the Tomball Memorial High School swim team his junior and senior years.

If he had the opportunity to swim for UT, he’d be the only Black person on the men’s roster, adding to the list of things that would make him a novelty.

Fortune is one of the only people in his extended family who knows how to swim, apart from his mother, father and sister. Many of the junior’s aunts, uncles and cousins suggest that he gives them lessons.

“As much of it is a joke, it’s really not,” Fortune said. “It’s pretty serious.”

Had he never taken lessons, Fortune might have been among the 64% of Black children who cannot swim, a statistic the USA Swimming Foundation found in a 2017 study. In comparison, 40% of white children cannot swim.

The racial gap is more visible on the starting block. Simone Manuel became the first Black American woman to win an Olympic gold medal in swimming after taking first in the 100-meter freestyle at the 2016 Rio Olympics. The 24-year-old from Sugar Land, Texas, was one of three Black people on the 47-member U.S. Olympic swimming team that year.

Fortune, who said his parents are friends with Manuel’s dad, remembers seeing the star swimmer break records at club meets he competed in. He was happy to watch her achieve so much success as a Black woman in swimming and representative of the Houston area.

When Cullen Jones won a gold medal as a member of the 4×100-meter freestyle team at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, Fortune felt a similar sense of pride.

“Seeing a Black guy on the podium swimming for Team USA, I think that’s something that kept me going when I was younger,” he said.

Despite the recent success of Black swimmers on the world stage, representation is lacking in the sport, fueling the stereotype that Black people can’t swim. One myth suggests that Black people have heavier bones, making them unable to float, but history says otherwise.

In the 15th century, European explorers witnessed sub-Saharan Africans swimming in coastal and river villages, according to the International Swimming Hall of Fame. Jim Crow era segregation, fueled by stereotypes that Black people are sexually dangerous and carry illnesses, unraveled the aquatic culture of Black people in the United States.

This often-violent racism limited their opportunity to swim, wrote professor Jeff Wiltse in “The Black-White Swimming Disparity in America: A Deadly Legacy of Swimming Pool Discrimination.”

“In southern and border-state cities, segregation was officially mandated,” Wiltse wrote. “Public officials relegated Black residents to one, typically small and dilapidated, pool, while whites had access to many large resort-like pools.”

Today, Black children between ages 5-19 are 5.5 times more likely to drown in swimming pools than their white peers, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

When Fortune was born in 2000, his mother said she constantly heard about babies in the Houston area drowning in pools.The family had a pool in the backyard, but Nina Fortune said she was the only one in the household who could swim at the time, as her dad took her to a pool at a YMCA in St. Louis, Missouri, where she grew up. Fortune’s father, who hails from Trinidad and Tobago, loved the water but had limited swimming skills, she said.

Fortune immediately took to the water after his mother signed the two of them up for Mommy and Me swim classes.

Nina Fortune is comfortable in the pool too, unlike her friend from St.Louis who only ever sticks her toes into the water. She learned several new strokes and techniques in a master class she took to pass the time as she waited for Fortune to finish his lessons. Sometimes she competed in adult swim meets where she stood out just like her son.

“If you walk into the mall, everyone has on clothes. It’s not a big deal,” Nina Fortune said. “Now imagine everyone had on a swimsuit. They all look alike, and you look different because your skin is so dark … You just feel so out of place.”

Alyvia Beaudion, Fortune’s former teammate, said it took a near-drowning experience when she was around 3 years old for her parents to enroll her in swim classes.

In addition to the microaggressions people would direct at her as one of the lone Black swimmers on her team, the college junior said dealing with chlorine-damaged hair was a challenge. Some hair products she used to combat the problem made her swim cap slip off as she raced.

“Black women often do have the issue with getting our hair wet and stuff, so it does make it hard to navigate,” Beaudion said.

Beaudion continues to swim at Bryant University in Rhode Island, but most of her family members stay out of the pool.

Fortune said he thinks many Black parents don’t take their kids to the pool because of their own reservations about the water, but knowing how to swim can be a matter of life or death.

“It’s cool that more and more Black people are lessening that fear,” he said. “They are wanting to learn because it is essential and you never know when swimming is going to help you.”